Wild Serenity Class - 2006

Notes from September 14 2006

Tonight again theme emerged of the damage we can sustain from being in meditation groups, with their primitive understanding of what the chakras are and their master-slave model of the guru-disciple relationship.

Notes from Wednesday, August 31

It's so odd, the boundary invasions that are common in alternative health and meditation circles. It's almost as if ignorant and slightly malevolent males are pretending to be physicians of the soul, and just cutting people up.

We all got in to the energy dynamics of saying NO, and perceiving the instinctive healthiness of setting boundaries, saying no, and moving away.

Tonight one of the themes was the damage people had experienced from being around gurus, evil chi gung "healers," and meditation teachers who play with energy and unknowingly fry their student's chakras and nadis.

People discussed the stage they are at currently. One person is more than three years along, since she left the guru, and she is begininnig to feel like herself again. It was as if the guru ripped out one of her chakras when she did not do his will.

With another person we invented exercises to give her a chance to reclaim her boundaries, and establish her sense of space.

Notes from Wednesday, July 27, 2005

I don't remember most of the class! If you have any notes, email them to me and it may prompt my memory. I do remember we did the giving/receiving exercise, which I invented on the spot.

Update - several people sent me notes, which I haven't entered yet.

Notes from Wednesday, July 13, 2005

We can consider meditation to be paying attention to our relationship with life, for example to the flow and pulsation of life flowing through us.

We began with a meditation in which we wondered, "What is breath, anyway?" Everyone talks about breathing, but what IS it? And how do I know I am breathing? What is the means through which I perceive the breath?

By the way, we did not talk about it, but we perceive breath and life through all our senses. We have over a dozen internal senses,including balance, oxygen level in the blood, temperature, motion, joint position. In perceiving the flow of breath through the nose, for example, you can tell - check this out now - the temperature difference between the inbreath and the outbreath. The mucous membranes in your nose are very sensitive to touch, and smell, and temperature, and motion. Then, for example, there is a tiny shift in your balance, in joint position, as your body expands on the inbreath.

Let's go back to the attitude of simply asking ourselves, "What is breath, anyway?"

Open to Wonder

This attitude can be called curiosity, inquiry, or wonder. It's a gentle embrace, a light touch, a respectful approach to the wild animal that is the self.

You can approach an everyday phenomenon such as breathing in the way you would a strange and wonderful animal. As if you were in the wilderness and woke up to find a horse standing near you, breathing. You gently walk over and with infinite respect and delight put your hand on her neck. You can explore your own breathing in this way.

Open to surprise, delight, wonder, and learning something new in every moment.

To go there, to enter the everyday and perceive it afresh and new, we have to give up artificiality. We have to give up imposing any supposedly "superior" or "devotional" or "spiritual" way of perception, even though they seem superior. We have to just be our natural selves and trust our instincts.

Applying this to meditation, if we think meditation is spiritual and devotional, then we probably won't want to do it. But if you take an attitude of wonder, a willingness to be surprised, and a little selfishness and naughtiness, then you may be surprised that you want to meditate and find time for it.

Unguarded Attention

Unguarded attention. When we are willing to be surprised by what we experience, that means we are open. In practical terms, we can only be as open as we are fearless.

What kind of philosophy supports you in being fearless in facing your inner life? What comes up in meditation to be faced is the same stuff you deal with in your dreams and when resting.

Attention to the Rhythm of Life

What we were exploring tonight in the meditation was an innate and natural meditation. A good working definition of meditation is "paying restful attention to the rhythms of life renewing itself."

When meditating, we pay attention. Paying attention is not an effort if we are interested in what we are attending to. And what is "being interested?" We are interested in things and processes that have value to us. And there are times when simply enjoying the flow of life through our bodies, which is what breathing is, can be very interesting.

Paying attention in a restful way means that we do not work at it. We allow ourselves to enjoy something. Naturalness is important because if we force anything, then we won't be resting, and if we are not resting during meditation, then it won't be as rejuvenating. Meditation that is not rejuvenating is like when sleep is not rejuvenating – you don't get what you need from it. This happens. A lot. But I don't believe in encouraging it.

The rhythms of life. Meditation is often thought to be about stillness but actually the techniques point us to the wave motion of life, and the sense of stillness in motion that can appear when we are loving waves. What is a breath meditation? Enjoying the flow and rhythm of breath, which flows in, turns, then flows out, every 5 or 6 seconds, all day and all night every night, as long as we live. What is a mantra meditation? Attending to a sound, a vibration, which is sound waves.

You can pay attention to something that appears to be still, for example a geometric diagram such as a cross, triangle, circle, mandala or yantra. But even there, the geometry is not just stillness – you, a living, vibrating being are contemplating a fixed form and interacting with it. Your relationship with that diagram can be vibrant and exciting and calming.

The Play of Opposites

Margaretha, when speaking of her meditation experience, made the infinity symbol with her hands.

∞

This is one of the main symbols of Instinctive Meditation. One day in the early 1970's, I noticed that meditators made this symbol spontaneously, without even noticing it, when speaking from the heart about their meditation experience, when they have been doing a technique that suits their individuality.

This symbol is so beautiful and graceful - both when people make it with their hands, and as a visual symbol of infinity. For meditators, it speaks of the play of opposites, breathing in and breathing out, attention flowing to the outer world and then to the inner world and then to the outer world again. Individuality and universality. Relaxation and excitement. Resting and alertness.

Here is a link to About.com on the infinity symbol: "The mathematical symbol for infinity is called the lemniscate. The infinity sign was devised in 1655 by mathemetician John Wallis, and named lemniscus (latin, ribbon) by mathemetician Bernoulli about forty years later.

The lemniscate is patterned after the device known as a mobius (named after a nineteenth century mathemetician Mobius) strip. A mobius strip is a strip of paper which is twisted and attached at the ends, forming an 'endless' two dimensional surface.

The religious aspect of the infinity symbol predates its mathematical origins. Similar symbols have been found in Tibetan rock carvings; and the Ouroboros or infinitysnake, is often depicted in this shape. In the tarot, it represents the balance of forces and is often associated with the magician card."

The Syzygy of Inner and Outer

There is an ancient word for union of opposites, yeug. This root-word is from Indo-European, the proto-language that many modern languages evolved from. Yeug means a bond, an integration, a link, and it shows up in many words we use everyday: join, joint, adjust, junction, juncture, conjugal. It's also there in jugular, conjugate, subjugate, jostle, joust, and juxtapose,

And there is a nifty, but weird-sounding word with yeug in it, that has lots of meanings: syzygy.

When the opposites are loving each other, it is called syzygy. This strange-looking word with two y's and a z in it is Greek for marriage, union, or conjunction. It also refers to the alignment of planets, as when the sun, the moon and the Earth are lined up.

If you look at the word again, what does that ygy look like? Turns out that it is from the same root as the word yoga. This makes sense because yoga is another word that means union.

Syzygy really means the same thing as yoga. And it's a Western word.

Syzygy is pronounced SIZ AH GEE, as far as I can tell. Here is a link to syzygy in the American Heritage Dictionary. This is a fabulous resource for words. Get to know it.

Breaking the Spirit

Meditation is natural – your body knows how to do it. It's an instinct. But you can mess it up – if you add anything unnatural to what you think of as your technique, then your inner nature will resist doing that. The natural animal in you will resist being "broken."

In the past, people talked of "breaking a horse." They tried to break the horse's spirit. And in meditation, it was the same – meditation was construed as a process of breaking your own spirit.

There is a series of interlocking concepts designed to help you break your own spirit:

- break the ego

- kill your passion

- break the chain of desire into action

- cultivate detachment

- turn away from materialism

These have been repeated so often, for so many centuries, that they have come to be accepted as "spirituality." But these are only one form of spirituality, a very legitimate form. It is called the renunciate path, because it is defined by renouncing everything. This is the definition of what monks and nuns do – they take vows. The vows generally are 1. Celibacy, 2. Poverty, and 3. Obedience.

If you are going to live in a monastery or a nunnery, it is appropriate to take vows. Just for the sake of crowd control. In most cultures, you can't have dozens or hundreds of people living together in close proximity in a spiritual institution and allow them to openly have sex, have them openly gloat about how much the temple is making in donations, and have them be all uppity in general.

And of course any of us can have the urge to give up sex, give up working to make money, and give up our independent path through life and surrender to a Fearless Leader, a dominant male or dominant female.

For certain people, in certain phases of their lives, it is appropriate and a form of spiritual adventure to leave behind their sense of self, their identity, and to sacrifice some of their instincts in order to live out others. These people have an urge to get rid of their humanity.

When meditation is approached in this way, it feels like a "work against nature." There as a Latin term, Opus contra naturam, which was used by alchemists in the past and Jungians today to refer to this Work - opus, Against - contra, Nature - naturam.

As an exercise some day, paste work against nature or Opus contra naturam into a search engine and look at what hits you get.

When we work against nature, it feels like a struggle, a heroic quest. Man against nature. How valiant. Sometimes it works, and when the person has given up sex, given up their individual identity, given up their name, given up their independent willpower, given up possessions, and given up the will to live, all their life energies sometimes become focused on the spirit world, and they become radiant with love. This happens sometimes. And sometimes the person is just depressed for a long time.

Amputation of Worldly Attachments

Our word, meditation shares the same root as medicine. The Latin root meditarai, which means, "to attend to, to restore balance." Going deeper, the med of meditation relates to "take the measure." You can see this in medicine where doctors, even in the ancient world, would take the pulse of the patient, feel the rhythm of their heartbeat. They would listen to the person breathing. When you think about it this way, you can see how related medicine and meditation are.

In medicine, if the person has a leg that has been smashed, and has gotten infected, and turned to gangrene, then and only then is it appropriate to cut it off. It is called medicine, under certain circumstances, to cut off someone's leg or arm. And the skill of medicine is to know how to do that and only do that when absolutely necessary. We don't call it medicine when you take a saw and hack off a healthy arm or leg. We call that evil, a crime.

The meditation traditions are ancient, and they have seemingly preserved every technique ever used by anybody anywhere. What they have not preserved as well is the knowledge of which technique goes for which situation. Consequently, techniques for self-amputation are being taught to people with healthy arms and legs.

People who have families and jobs are being taught to "detach" from themselves and from their loved ones, as if this is spirituality. But it may not be spirituality, only detaching – a kind of emotional amputation.

In spiritual circles, what works about amputation, about training people to become alienated from themselves, their friends, and their families, is that they then become deeply dependent upon the guru, the ashram, the lineage and the teachings. As people detach from their own egos, they become subservient to the guru's ego, and gurus have huge egos. They tend to be multimillionaires, drive around in limousines, own huge houses, and demand that other people bow down to them and worship them. If that is not a grandiose ego, then what is?

I say this "works" because it works to perpetuate the system of which the guru is a part – the ancient culture in which domination and submission are thought to be spiritual. When people cut themselves off from their friends and families and even their own impulses, then the guru becomes supremely important – the only real relationship in their lives. They start to obsess about the guru. The guru becomes their invisible friend, floating in space two feet above and in front of their head. The guru will scowl at you if you think about going dancing. The guru scowls at you if you are kissing someone.

It is true that detachment is what Buddha did and taught. The day his son was born, he looked at his wives sleeping and was disgusted with them. He thought they all looked hideous, so he ran away in the middle of the night and went out to the forest and starved himself. Apparently for Buddha, abandoning his family led to interesting insights. But his family was still there in the palace – they were not homeless. And even though Buddha advocated the "path of homelessness," he always had that palace to go home to. He was raised to be a king and he was always a king, at every moment.

So for Buddha, abandoning his family was one thing. As if Brad Pitt were to leave his family in a 50 acre mansion in Malibu, with 60 million dollars in the bank to pay for everything, and go sit on a hillside nearby, fasting and praying. He would still be in Malibu, still be Brad Pitt even if he shaved his head and did not bathe for two years.

For modern people, practicing "detachment" is a random process, sort of like taking a knife and hacking away at your skin at random. Detachment is a natural process, speeded by grieving, but it happens all the time as part of life. Mothers with babies are very attached, and babies are attached to their mothers. And yet everything changes, all day long, every day. The baby starts moving around on her own, crawling, then walking, and wants to be independent. Gradually, changing every day, over a period of years the baby becomes more and more independent. As a matter of fact, the more each stage of development gets fulfilled, the more independent the child becomes. So mothers and babies both learn about attachment and detachment every minute of every day. It's a dance.

So it is not spiritual to just practice detachment. Unless you are a monk, who has taken a vow to die to his old self, change his name, obey his authorities WITHOUT QUESTION, never have sex ever again, never own anything ever again. Monks practice detachment because that is their path.

Practicing detachment is intrinsically depressing because it involves loss. It is as if some part of you dies. This can lead to rebirth, a spiritual rebirth, or it can lead to being dead inside.

From a Buddhist site: "Pabbajja is Going forth, namely from the household life to the homelessness of a Buddhist monk. The Pali word Pabbajja is also the term for the first ordination bestowed for entry into the Buddhist monastic Order (Sangha) by which the candidate becomes a Novice or Samanera."

From another site, "Renunciation and Deliverance: The key move that charactrizes the act of becoming a monk is renunciation, going forth from the household life into homelessness. Homelessness is not absolutely essential for this work, true renunciation is an inner act, not a mere outer one. But the homeless life provides the most suitable outer conditions for practising true renunciation. But anyone who has correctly grasped the drift of the Dhamma will see that the path of renunciation follows from it with complete naturalness.

"The Buddha teaches that life in the world is inseparably connected with dukkha, with suffering and unsatisfactoriness, leading us again and again into the round of birth and death.

"The reason we remain bound to the wheel of becoming is because of our attachment to it. To gain release from the round we have to extinguish our craving. That is the highest renunciation, the inner act of renunciation. But to win that attainment we generally must begin with relatively easy acts of renunciation, and as these gather force they eventually lead us to a point where we no longer are attracted to the pleasures of the world. When this happens, we become ready to leave behind the household life, to enter upon homeless state in order to devote ourselves fully to the task of removing the inner subtle clinging of the mind."

For the 99% of humanity that are not monks, the path is different. Monks, somewhat disparagingly, call us "householders."

Whatever we call ourselves, the path for people who have friends, jobs, and a life, is in some ways the opposite of the monk's path.

But we are all influenced by the monks when we think about meditation, because they have defined the terms with which we think. They have spent thousands of years creating these thoughtforms.

The vows are radioactive, I think. They are a living sacrifice, and the monk or nun gives off rays of renunciation which includes dissociation and disgust.

Householders who are around monks have to beware lest they become dissociated, adrift, and disgusted with life.

If you are not a monk or nun and you are influenced by the vows, it's not called celibacy, poverty and obedience. It's lonely, broke and submissive.

Meditation For People Who Live in the Real World

Instead of using the lame term, "Householders," let's make up another term, like, "People who live in the world." This refers to people who have friends, families, jobs, and homes.

On this path, we evolve through the experience of:

- Intimacy

- Attachment

- Passion

- Spontaneity

- Naturalness

Don't Belive A Word I Say About Passion

Get to know these concepts, study them, make them your own. Do not believe me, because these terms all refer to the way you inhabit your body and the way you are in relationship with the life force. So these words refer to an intimate inner marriage, the texture of how you will experience your own existence. This is too important for belief – work these words, doubt them, wrangle with them, grab them, make them your own. Doing so will help you have healthy boundaries in relationship to the vast and tireless propaganda machine

For people who have jobs, meditation needs to be luxurious and restful. Meditation practiced in this spirit feels intimate, and we can define meditation as intimacy with the self.

Intimacy – In To See Me

Intimacy means closeness, and has the sense of being involved in a cozy, familiar, way. It is the opposite of detachment.

Intimacy is a continually changing, infinitely varied experience. If you have a friend, the texture of that relationship changes from moment to moment. There may be an unchanging, underlying commitment you each have to the relationship, but the emotional tone changes constantly. You come together, and then separate.

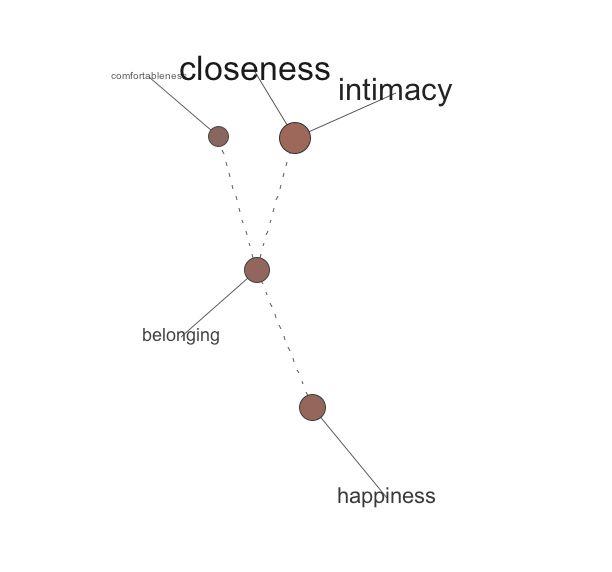

From the Visual Thesaurus:

There is always a play, an interplay of space or separation, and closeness. But usually, having distance and being detached are not the be-all-and end-all of the relationship. Detachment is not an ideal you are trying to pull off in the midst of a friendship. Householders are continually balancing intimacy and distance, finding the appropriate amount of closeness to each person in each moment. Householders tend to have many relationships going on simultaneously.

Attachment refers to the bonds we form with others. Bonds of affection. Householders work with attachments, honoring them.

Passion

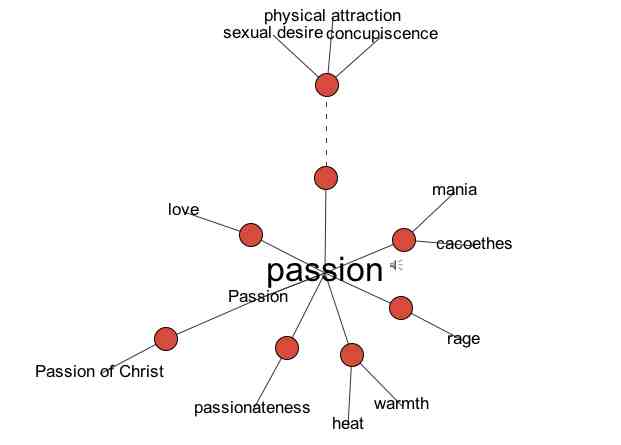

Passion is an interesting and very complex word.

Visual Thesaurus shows the relationship of passion to other words:

From Latin, passus, past participle of pati, to suffer.

From the American Heritage Dictionary

SYLLABICATION: | pas·sion |

NOUN: | 1. A powerful emotion, such as love, joy, hatred, or anger. 2a. Ardent love. b. Strong sexual desire; lust. c. The object of such love or desire. 3a. Boundless enthusiasm: His skills as a player don't quite match his passion for the game. b. The object of such enthusiasm: Soccer is her passion. 4. An abandoned display of emotion, especially of anger: He's been known to fly into a passion without warning. 5. Passion a. The sufferings of Jesus in the period following the Last Supper and including the Crucifixion, as related in the New Testament. b. A narrative, musical setting, or pictorial representation of Jesus's sufferings. 6. Archaic Martyrdom. 7. Archaic Passivity. |

ETYMOLOGY: | Middle English, from Old French, from Medieval Latin pass |

SYNONYMS: |

So Passion has the meaning, "to suffer." But what is suffer? Suffer does not just mean to feel pain; it also means to permit to allow, to endure.

Suffer

TRANSITIVE VERB: 1. To undergo or sustain (something painful, injurious, or unpleasant): “Ordinary men have always had to suffer the history their leaders were making” (Herbert J. Muller). 2. To experience; undergo: suffer a change in staff. 3. To endure or bear; stand: would not suffer fools. 4. To permit; allow: “They were not suffered to aspire to so exalted a position as that of streetcar conductor” (Edmund S. Morgan).

ETYMOLOGY: Middle English suffren, from Old French sufrir, from Vulgar Latin *suffer

Visual Thesaurus:

Spontaneity

Naturalness

For "householders," naturalness means, among other things, that you do not have to be devotional, good, spiritual, or nice when you meditate. You can be tired, cranky, horny, rebellious, and selfish. You can meditate because it feels better than a smoke, a shot of vodka, or a TV show.

more later . . .